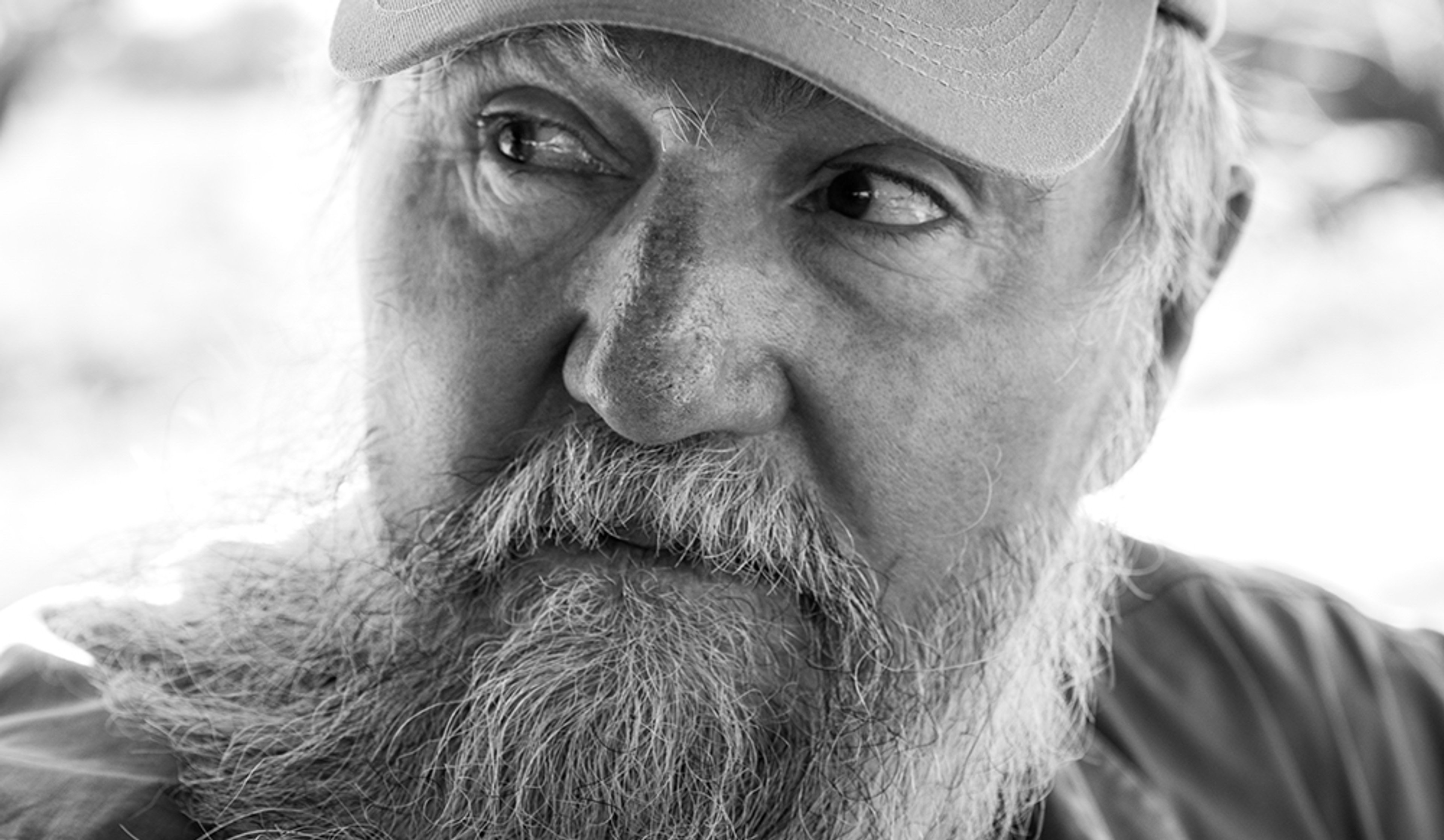

Map Ives

Conservationist Map Ives’ story is a classic tale of character and calling. At its core is the belief that each of us is called to a certain destiny. Plato and the Greeks called it a daimon, the Romans saw it as genius, and the Christians likened it to a guardian angel. In Map’s case, it was unequivocal and asserted itself from an early age.

"I spent my childhood in the wilds of Francistown, Botswana," says Map, whose name is an acronym for Martin Antony Paul Ives. Back then (in the late '50s), Botswana had a population of 400,000, compared to the more than 2.5 million people who live there today, and Francistown no more than a few hundred people. "It was a magical place," Map recalls. "There were wild animals in close proximity to the village, and I was lucky to learn firsthand from local bushmen about plants and animals, not to mention the art of tracking and living off the land."

A defining moment for Map came in 1964, when he saw a short black and white documentary about a wildlife rescue mission called Operation Noah in what was then Rhodesia. "A wildlife catastrophe had ensued after the damming of the Zambezi floodplain to create Lake Kariba, with thousands of animals taking refuge on ever-shrinking islands in the Kariba Gorge," explains Map. "I became fascinated by legendary game ranger Rupert Fothergill, who led the mission to save more than 6,000 animals, 44 of which were rhinos. I remember watching, spellbound, as he and his team captured a rhino by tying it down and floating it on a raft to safety. From that moment on I wanted to be him—I still do."

Such vicarious aspirations turned out to be wholly unfounded, for Map is a full-blown legend in his own right. Having worked more than 40 years in the field of conservation, his greatest passions, namely the Okavango Delta and the plight of rhino, keep him busy. Not only was he instrumental in conceiving the development plan for the Okavango Delta (an UNESCO World Heritage Site) but in 2014 he was made the National Rhino Coordinator for Botswana. He is also Environmental Director for Wilderness Safaris.

Map’s view has always been that if the Delta can be utilized on a sustainable basis for the benefit of Botswana, then it can be protected for the long term. "I’m glad to say that our low-volume, low-impact, non-consumptive tourism model has kept the Delta pristine and wild," says Map. His work with rhinos is no less impressive. What started out as a rhino reintroduction project has developed into a sophisticated joint operations mission with Botswana, the safe haven for the critically endangered black rhino.